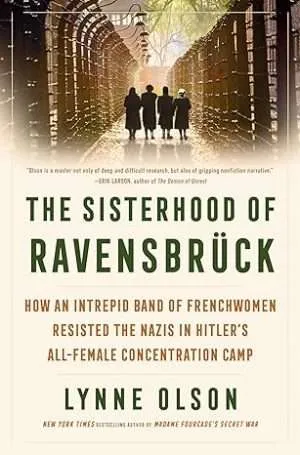

The extraordinary true story of a small group of Frenchwomen, all Resistance members, who banded together in a notorious concentration camp to defy the Nazis

Decades after the end of World War II, the name Ravensbrück still evokes horror for those with knowledge of this infamous all-women’s concentration camp, better known since it became the setting of Martha Hall Kelly’s bestselling novel, Lilac Girls. Particularly shocking were the medical experiments performed on some of the inmates. Ravensbrück was atypical in other ways as well, not just as the only all-female German concentration camp, but because 80 percent of its inmates were political prisoners, among them a tight-knit group of women who had been active in the French Resistance.

Already well-practiced in sabotaging the Nazis in occupied France, these women joined forces to defy their German captors and keep one another alive. The sisterhood’s members, amid unimaginable terror and brutality, subverted Germany’s war effort by refusing to do assigned work. They risked death for any infraction, but that did not stop them from defying their SS tormentors at every turn—even staging a satirical musical revue about the horrors of the camp.

After the war, when many in France wanted to focus only on the future, the women from Ravensbrück refused to allow their achievements, needs, and sacrifices to be erased. They banded together once more, first to support one another in healing their bodies and minds and then to continue their crusade for freedom and justice—an effort that would have repercussions for their country and the world into the twenty-first century.

CW/TW – The survivors of the camp talk about their PTSD, graphic conditions in the camp are described, the horrific surgeries conducted on the Polish “Rabbits” are described, the sadistic actions of the guards in the camp are described.

“There is no such thing as an uncivilized people.”

Dear Ms. Olson,

Before I’d even read the blurb, I asked to review this book based on the two other books of yours that I’ve read. I also wanted to read more about this camp because of another book, “Rose Under Fire” that I read years ago which was mainly set in the camp. I’ll be upfront with readers that at times this was not easy to read. Take the CWs/TWs seriously. But I learned a lot and by the end, found it uplifting.

“We are here to be killed.”

The book focuses mainly on some of the French women who were arrested for their actions during WWII as well as the Polish women whose legs were butchered in experiments (hence the term they used for themselves The Rabbits). Other nationalities are briefly mentioned as there were many different ones since this camp housed (mainly) women. We learn a bit about the prewar lives of the French women and what they did before being arrested. Then comes the descent into hell. Knowledge of what to expect saved sanity and friendships saved lives. The “buddy system” kept women alive with not only physical but emotional care and support. Bonds were formed that would last lifetimes.

She advised the newcomers that the single most important thing in their lives now was to form tight bonds with one another. Without that, none of them would survive. They must also do their best to stand up to the Germans. Still in shock from her first view of the camp, Geneviève de Gaulle was “amazed and filled with admiration” by Germaine’s analysis. “The first thing she did was give us knowledge,” she said. “That was a lifesaver for me. When you understand, you can fight back.”

I was surprised when I realized that the time spent in camp was only about half of the book. What was left to tell? Well, the return to France and the attempts of these women to put their lives back together in the face of increasing public desire to put the war behind and forge a new future. People in general also didn’t want to hear the details, leaving the survivors to talk amongst themselves and support each other – again physically, mentally, and financially. Some found life partners, often men who had worked in resistance and also been incarcerated. One woman made it her mission to bear witness at the post war Ravensbruck trials to try and ensure that those guilty paid for what they had done.

“I’m a Pole, and I’m going to die. This medicine will help you survive. My father sent it to me through the underground. He heard about the infections in my operated legs and he thought this would help them heal. It’s of no use to me if I am going to die, but I want you to have it so that you can live and tell the world our story. You must make people aware of what they did to us.”

Unlike the male groups of survivors, usually the women didn’t look backwards but tried to take their experiences and help others who were marginalized, in need, and without public support. One vow that had been made, to keep the Rabbits alive in the face of the determination of the Nazis to kill them and hide the living evidence of what had been done as well as assist them to get help and reparations, had been partly accomplished in the final months of the war when the entire camp banded together to save these women. The second part of the vow would take over fifteen years, a public and media campaign in the US, and lots of pressure on the West German government to achieve.

Ferencz, meanwhile, was on the phone to the German ambassador several times a week. “We’ll keep on marching,” he told the ambassador at one point, “and we’re going to continue to hammer the hell out of you until you take a more moral position.”

These survivors never stopped working to better the world and would call out injustices – even by their own government in Algiers – when and where they saw them. Their experience also led to an amazing event. To support their spirits and help them laugh at the darkness around them, one woman had written a tragi-comic operetta-revue while her fellows covered for her work which if discovered would probably have gotten her killed. Decades later, a theater group in Paris resurrected it and staged it to critical acclaim. Le Verfugbar aux Enfers has since been performed in several countries including at a university in Maine for which the cast all shaved their heads.

“No one better than us, the deportees, knows what it’s like to be deprived of the deepest rights of a human being, to be treated like nothing, to be controlled, to be humiliated,” Geneviève de Gaulle Anthonioz declared at one ADIR annual meeting. “We will fight to protect others who are in that same situation until we no longer draw breath.” She and others in the group focused on those who had been most forgotten in modern society—the poor, the homeless, the elderly, children, refugees.

What they endured forged lifelong bonds of sisterhood. Without those, many of these women freely admit that they probably wouldn’t have survived. The nightmares followed many of them all their lives. But they took the experience and turned it into something positive in what they accomplished publicly and privately. B+

~Jayne

Interviewed for a documentary more than fifty years after the war, Geneviève remarked, “I don’t think our friendship can be described. I always say that she’s my sister.” Jacqueline, for her part, thought their bond “was even stronger than blood ties.” She added, “It was essential [at Ravensbrück] to have someone as close as we were to each other. It changed everything.”